29

Introduction and Theory |Inadequacy of Current Visualization Methods

28

Introduction and Theory |Inadequacy of Current Visualization Methods

By observing the delta in time between these developments, it can be seen how rapidly technology has progressed in the past hundred years relative to human history. Even before the observation of Moore’s Law, within 30 years, computation production went from the first efficient transistor to an agenda of producing smaller and cheaper computers. Comparing this to the few hundred years between the development of linear perspective and photography, it can be presumed just how fast visualization progression will not only continue but accelerate from this point onwards.

Schindler views this technological progress in the context of timber construction as waves of development “divided into three essential production technologies in the history of mankind: hand-tool-technology, machine-tool-technology, [and] information-tool-technology.”[9] He states, “to this extent the three ‘waves’ of technology are not to be understood as competing, incompatible principles, but rather as the gradual substitution of formalized physical and later also formalized intellectual operations by machines. Man is not replaced, but revalued. His function shifts from processor to process designer.”[10] This view highlights how the progression of these new technologies can gradually allow the outsourcing of tedious work away from low-efficiency humans to high-efficiency computers, thus not only improving efficiency in mundane tasks but also allowing humans to focus on more purposeful work—both of which can drive progression even faster than it is now.

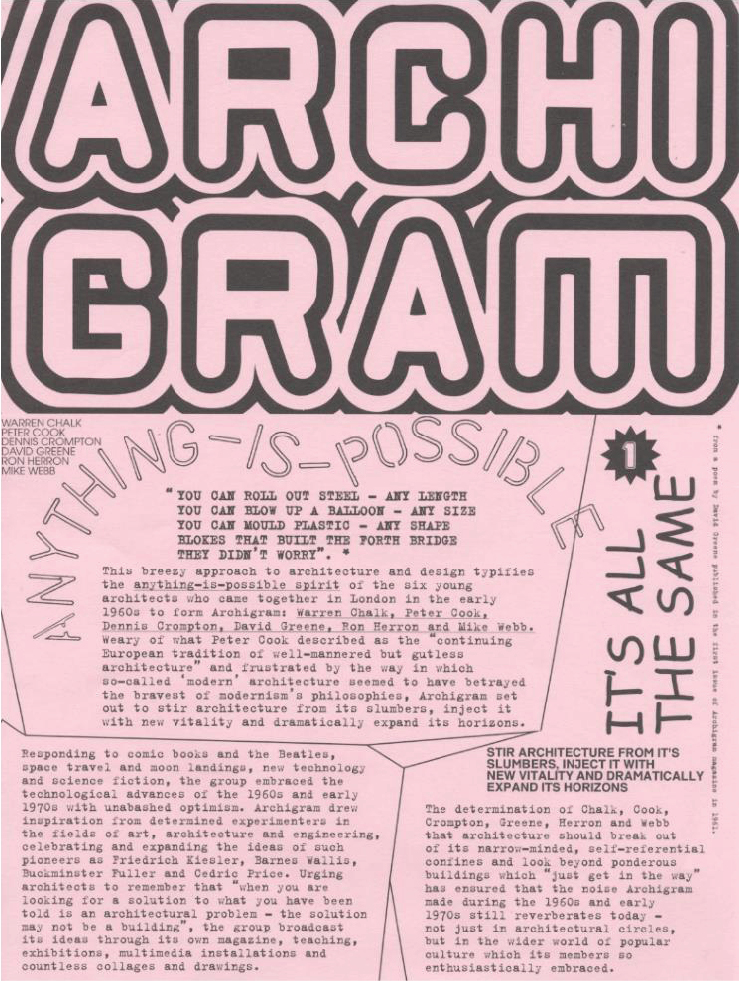

The potential ramifications of these new technologies generated excitement, invoking avant-garde movements such as neo-futurism, where designers began thinking new ways of programming spaces, facilitating new architectural ideas that transcended norms. The London-based architecture group Archigram was one such example, where they published a series of magazines throughout the 1960s, featuring futuristic concept designs on what they imagined computation could bring to architecture. (Fig. 1.2.7 - 11) Within Beyond Archigram, Hadas Steiner notes an excerpt from Design Quarterly in an IDEA conference pamphlet in 1966 that “the strength of Archigram’s appeal stems from many things … But chiefly it offers an image-starved world a new vision of the city of the future, a city of components on racks, components in stacks, components plugged into networks and grids, a city of components being swung into place by cranes.” [11] This excerpt highlights the reason for Archigram’s success, which stems from—amongst many cultural drivers such as new technologies and the world wars—satisfying the world’s aspirations for the future; how this new mindset of embracing change allows the mere idea of new technologies to drive new forms of creation, further reinforcing the observed influence of new technologies on the world.

9 Schindler, “Information-Tool-Technology: Contemporary digital fabrication as part of a continuous development of process technology as illustrated with the example of timber construction,” 2.

10 Schindler, “Information-Tool-Technology: Contemporary digital fabrication as part of a continuous development of process technology as illustrated with the example of timber construction,” 17.

11 Hadas A. Steiner, Beyond Archigram: The Structure of Circulation (New York: Routledge, 2009), 202.

Archigram Information Tear-off Sheet

From “Archigram: Tear-off Information Sheets,” BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art, accessed December 18, 2019, http://balticplus.uk/archigram-tear-off-information-sheets-c8292/.