27

Introduction and Theory |Inadequacy of Current Visualization Methods

26

Introduction and Theory |Inadequacy of Current Visualization Methods

Photograph of Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève by Bisson Frères

By Bisson Frères, from Neil Levine, “The Template of Photography in Nineteenth-Century Architectural Representation,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 71, no. 3 (January 2012), https://doi.org/10.1525/jsah.2012.71.3.306.

Figure 1.2.5 - 1.2.6

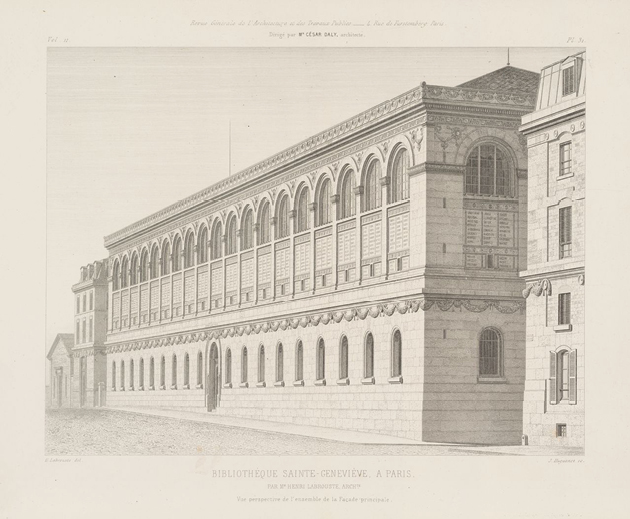

These figures shows how Labrouste removed all traces of human activity in prepara-tion of engraving the photo. In doing so, he reinforced the clarity of the design.

Perspective view of Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, traced from Bisson Frères’ photograph by Henri Labrouste, engraving by Jacques-Joseph Huguenet

By Henri Labrouste, traced from photograph by Bisson Frères, and engraved by Jacques-Joseph Huguenet, from Levine, “The Template of Photography in Nineteenth-Century Architectural Representation.”

This capability of portrayal was enhanced even further with the invention of photography in the 1800s.[5] In a drawing, every line is deliberate, but a photograph captures the location with context, whether accidental or deliberate. This aspect of photography gained it its credibility as a tool for documentation, as it was a way to confirm and validate, but at the cost of visual flexibility.[6] It wasn’t until French architect Henri Labrouste and his deliberate tracing of photographs that allowed the removal of unwanted features and the highlighting of important details to regain that visual flexibility. (Fig. 1.2.5 - 6) Neil Levine describes Labrouste’s tracings in The Template of Photography in Nineteenth-century Architectural Representation:

“Labrouste’s tracing of the photograph involved more than removing unwanted features. His redrawing highlighted important aspects of the building that were somewhat indistinct in the photograph. The lack of clarity of detail in parts of the photograph is ironic given the emphasis on the medium’s ‘precision’ and ‘exactitude’ in the photographic discourse. […] Labrouste built on photography’s putative strengths to give the image an even greater degree of precision, exactitude, and mechanical definition than the photograph itself provided. […] Finally, the removal of all trace of human occupation transformed the photographic scene into an abstracted, airless, uncanny representation of reality combining in almost equal measure the rational character of the building’s design with its pronounced structural expression.”[7]

Within this passage, Levine notes the irony of Labrouste’s tracings: how by removing features—thus reducing the clarity of the photograph—he was able to enhance the clarity of the building design by highlighting the “important aspects of the building.” This of course benefited greatly in architectural visualizations as it allowed designers to visualize what is important in the design while keeping the building within context—essentially becoming an early form of architectural rendering.

Although each of these advancements facilitated progression, none of them have influenced the modern world as rapidly and profoundly as digital computation. Since its conception in the mid-1900s, many industries conformed by moving towards digital mediums, changing not only architectural visualization, but the rest of the world as well. Christoph Schindler gives a brief summary of these developments in his dissertation Information-Tool-Technology: Contemporary digital fabrication as part of a continuous development of process technology as illustrated with the example of timber construction:

“William Shockley developed the first efficient transistor in 1947 at the US Bell Laboratories; in 1958 Jack Kilby started to cast integral circuits into a germanium ‘microchip’; and in 1970 IBM produced the first silicon ‘microprocessor chip’. From this point onwards the agenda was set to produce computers small and low priced enough to be built into machines to automate complex formalized processes economically.”[8]