23

Introduction and Theory |Inadequacy of Current Visualization Methods

22

Introduction and Theory |Inadequacy of Current Visualization Methods

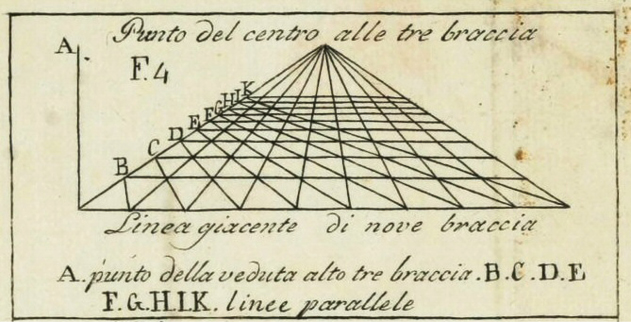

Vanishing point, depicted in Della Pittura by Alberti

By Leon Battista Alberti, Della pittura e della statua di Leonbatista Alberti (Milano : Società tipografica de’Classici italiani, 1804), http://archive.org/details/dellapitturaedel00albe.

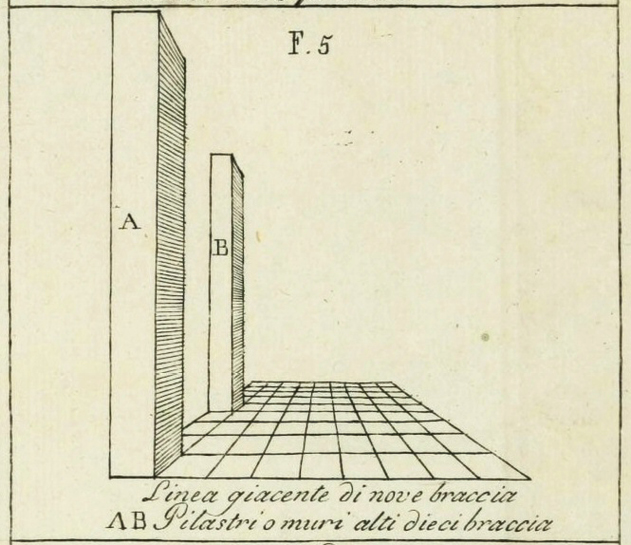

Perspective pillars on grid, depicted in Della Pittura by Alterbi.

By Alberti, Della pittura e della statua di Leonbatista Alberti.

Inadequacy of Current Visualization Methods

With these new forms of dynamic architecture comes increased complexity in both operation and design. As such, current visualization workflows must be updated to accommodate this development. Fortunately, technological progression benefits not only the construction of these new dynamic spaces but also the tools for designing and visualizing them. Richard Sennet states in The Craftsman: “We need to visualize what is difficult in order to address it. This is probably the greatest challenge facing any good craftsman: to see in the mind’s eye where the difficulties lie.”[1] From this, one can infer that visualization can facilitate access to complexity, which in turn will allow the development of new technologies that can develop even better visualization tools. This concept, where one development feeding into another as a cyclical progression is nothing new, as visualization methods have progressed as such throughout history.

The first of these progressive leaps in regards to architectural visualization was perhaps the development of linear perspective in the 1400s by Italian architect Filippo Brunelleschi.[2] This method was later documented within the treatise Della Pittura (On Painting) by Leon Battista Alberti[3] that established the preservation and accessibility of this knowledge to later generations. John R. Spencer noted within his translation of Alberti’s De pictura that “By substituting the pyramid for a cone Alberti made the one-point perspective system possible, for in pyramidal vision the size of the object seen varies as the height of the observer’s eye and the distance to the object. Although he was physiologically incorrect, Alberti made it possible to represent objects on a plane surface with greater apparent exactitude.”[4] (Fig. 1.2.1 - 2) Before this development, most art and visualization depictions consisted of mostly two-dimensional images with little attempt to portray depth or three-dimensionality, and where such attempts within medieval paintings, were exceedingly incorrect. (Fig. 1.2.3 - 4) With “this greater apparent exactitude” however, visualization evolved to better portray the dimensionality of the world and, in essence, the architecture within the world.

1 Richard Sennett, The Craftsman (London: Penguin, 2009), 230.